Part 03

Photo Credit: Mark A. Wilson Department of Geology, The College of Wooster

We have all known since our school days that the holy Ganga is the national river. But many of us are still ignorant about its plight. This article portrays a detailed canvas of a crying river in context to its pollution and future threats. Finally, it contours what can be done to mitigate the effects of imminent and impending danger.

So far in part 1 and part 2, we have understood why Ganga is such a special river and how it has become so miserable. In this part, we will look at the possible remedies.

Contents:

Solutions

Ganga was on fire once! In 1984, the river caught fire and continuously burnt for more than 30 hours. It was supposed to have occurred when a matchstick was tossed into it by a smoker in Haridwar. It is said that a toxic layer of chemicals was built on the river surface owing to discharges from a pharmaceutical firm[i].

Out of concern, an environmental lawyer and social activist Mr. M.C. Mehta filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court of India. He charged that government authorities had not taken effective steps to abate environmental pollution in the Ganga. But it was impossible to pinpoint the exact source of the problem. Upon the court’s request, Mr. Mehta narrowed his focus and chose Kanpur[i].

Mehta reasoned that “Kanpur was in the middle of the Ganga Basin, the reddish color of the pollution made the pollution highly salient, and the city seemed representative of many other cities in the Ganga Basin.” The court subsequently split the petition into two parts. The first dealt with the tanneries of Kanpur and the second with the city government. These are now respectively called Mehta I and Mehta II in legislative digests and are together known as the “Ganga Pollution Cases” – the foundational water pollution litigation in the Indian court system.[i]

Let me quote an excerpt here. ”In October 1987, the Court invoked the Water Act and Environment (Protection) Act as well as Article 21 of the Indian Constitution to rule in Mr. Mehta’s favor and ordered the tanneries of Jajmau to clean their wastewater within six months or shut down entirely. This was followed by a January 1988 judgment that required the Kanpur local municipal bodies to take several immediate measures to control water pollution: the relocation of 80,000 cattle housed in dairies or the safe removal of animal waste from these locations; the cleaning of the city’s sewers; the building of larger sewer systems; the construction of public latrines; and an immediate ban on the disposal of corpses”.[ii]

Since then, our government has spent several million rupees to curtail pollution in Ganga through different cleaning programs. For instance, in 1986, the Ganga Action Plan (GAP) phase I was launched to reduce sewage discharge. Seven years later, GAP phase II was launched which focused on the tributaries of Ganga. Finally, National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) was launched in 2009 for the cleaning and conservation of the Ganga[iii].

The government also launched the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) called the Namami Gange Programme in 2014. It is by far the most ambitious plan to conserve the Ganga and improve its water quality through an integrated conservation program including immediate, medium-term, and long-term activities. Several reputed international agencies such as Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), German International Cooperation (GIC), International Water Management Institute, and World Bank are involved in NMCG for financial and technical support based on their experience in river management[iv].

Results

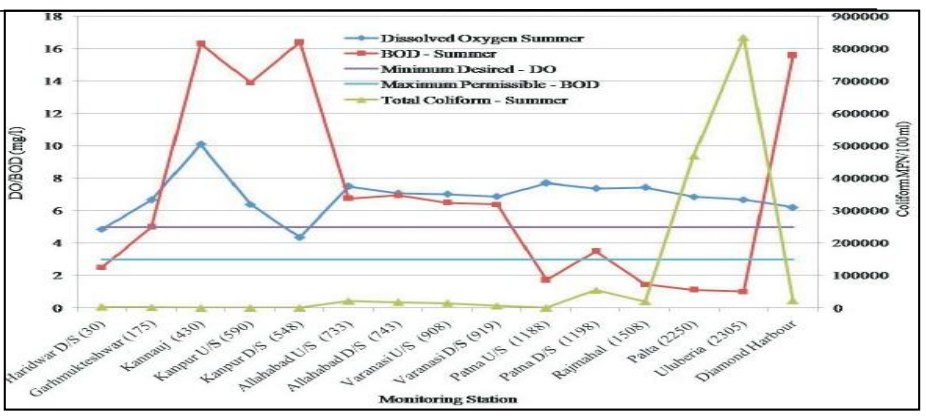

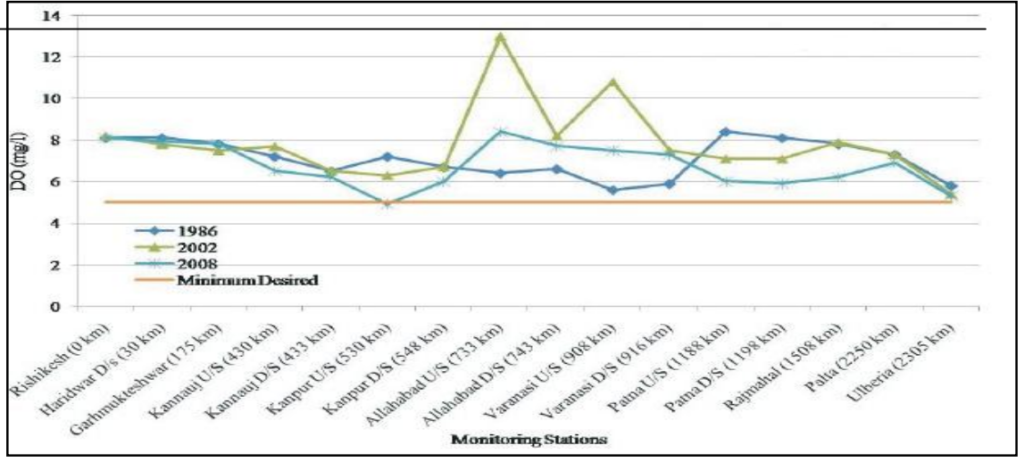

But these are all theories. At the end of the day, seeing is believing. Let us see how far the legislation and policies have become fruitful. A comparative study on water quality pre and post-GAP was carried out. We already know that low BOD and high DO indicate good water quality. In 1986, BOD ranged from 5.5 to 15.5 mg/l in the critical stretch from Kannauj to Varanasi. The same parameter’s values in 2008 from Kannauj to Kanpur and Allahabad to Varanasi were 2.9-4.1mg/l and 2.2-4.8 mg/l respectively, indicating improvement in water quality. DO levels in the Allahabad-Varanasi stretch were in the range of 5.9 to 6.6 mg/l in 1986. In 2008, the range had improved to 7.3 to 8.4 mg/l[v].

Picture credit: International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 2, Issue 1, January 2015

Picture credit: International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 2, Issue 1, January 2015

Improvement in water quality has also led to a reduction in infant mortality. A study from 2018 reported that 16-29 percent drop-in neonatal mortality rates due to the enforcement of environmental laws[vi].

Future scopes

Government enterprises seem to work but at a sluggish pace. Hopefully, local communities have come up with innovative and smart solutions to curtail pollution. Take for example, in the Philippines and Cameroon, members of the community called “Net-Works” directly sell end-of-life fishing gear and recovers the Nylon 6 content from the marine environment and sell it to the global supply chain. These, in turn, get recycled into products like carpet tiles, etc. The entire venture has boosted the economy in that region and has helped marginalized communities. Indians can also follow the example and help the government[vii].

We can also shift our attention to the ecohydrological approach. Growing crops that reduce soil erosion might turn useful. Special focus can be given to crops that are low maintenance but increase profits can help to raise the economic status of the farmers. Thus, they can resort to more cutting-edge technologies to conserve water.

Last but not least is awareness. We can certainly include a chapter on Ganga pollution in our school textbooks. Government can arrange more forums and educational shows about our lifeline Ganga. Government can also monitor the corruption of its officials on routine basis to make sure there are no financial constraints in the pollution abatement projects.

On a side note, there are still many scientific investigations left to be conducted. It is shocking to note so many dead bodies were dumped into the Ganga during the corona outbreak. Scientists are yet to monitor how that affected the water quality.

Conclusion

We can summarize that Ganga which once showed us the pathway to moksha is now a spiral staircase to hell. And for what only we human beings are to be blamed. Finally, we need to realize that our blind devotion is outright dangerous. Our unshaking faith that the Ganga is pristine as it was centuries back is seriously wrong. The only way we can get away from our old habits is open mindedness. Luckily the task is surprisingly not that difficult! Just a little bit of scientific awareness and restraint from age old advices will only do!

This part draws the curtain on this series. If you have missed the previous parts, check out the following links:

Author’s Bio:

Shrestha Chowdhury is currently working as a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Chemical Sciences at IISER KOLKATA. For her fourth and her longest blog on the TQR platform, she has attempted to pen down her thoughts on our holy and beloved river the Ganga. This project was an eye-opening journey for her both in terms of scientific temperament and spiritual context. She earnestly wants the dire state of the river to be recovered into its glorious and pristine form. Hope the readers enjoy the write-up!

References

[i] Do, Q.-T., Joshi, S., Stolper, S., Can environmental policy reduce infant mortality? Evidence from the Ganga Pollution Cases, Journal of Development Economics (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.03.001.

[ii] Do, Q.-T., Joshi, S., Stolper, S., Can environmental policy reduce infant mortality? Evidence from the Ganga Pollution Cases, Journal of Development Economics (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.03.001.

[iii] Environ Monit Assess (2020) 192: 221 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-8152-2

[iv] Environ Monit Assess (2020) 192: 221 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-8152-2

[v] International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 2, Issue 1 , January 2015

[vi] Do, Q.-T., Joshi, S., Stolper, S., Can environmental policy reduce infant mortality? Evidence from the Ganga Pollution Cases, Journal of Development Economics (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.03.001.

[vii] Science of the Total Environment 756 (2021) 143305